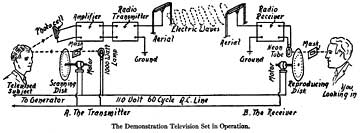

Mechanical Television Mechanical TV: How it works Mechanical TV uses rotating disks at the transmitter and the receiver. These disks have holes in them, spaced around the disk, with each hole slightly lower than the other. The camera is located in a totally dark room. A very bright light is placed behind the disk. The disk is turned by a motor, so that it makes one revolution every frame of the TV picture. In the Baird standard, for instance, the disk has 30 holes and is rotated 12.5 times per second. A lens in front of the disk focuses the light on the subject being televised. As the light hits the subject, it reflects into a photoelectric cell, which converts the light energy to electrical impulses. Dark areas of the subject reflect very little light, and only a small amount of electrical energy is produced, while bright areas of the subject reflect more light, and therefore more electrical energy is produced. The electrical impulses are amplified and transmitted over the air to the receiver, which also has a disk turned by a motor, which turns at exactly the same speed as the one at the camera (there are several methods of synchronizing the motors). A radio receiver picks up the video transmissions and connects to a neon lamp, which is is placed behind the disk. As the disk rotates, the neon lamp puts out light in proportion to the electrical signal it is getting from the receiver. For dark areas, very little light is put out; for bright areas, more light is put out. The image is viewed on the other side of the disk, usually through a magnifying lens. There are other methods of producing pictures using mechanical means, such as the mirror screw, mirror drum, and lens disk. For information on these systems, see Peter Yanzcer's website. |